The Atholl Papers: The Jacobite Rising of 1745

The Atholl family and the wider members of Clan Murray have a complicated relationship with Jacobitism; one of divided loyalties, which saw family and clan members pitted against one another in all three risings (1715, 1719 and 1745), in the name of either a Hanoverian king or the ‘Pretender,’ James Francis Edward Stuart. William, Marquess of Tullibardine and the eldest son of the 1st Duke of Atholl, was the most unrepentant of Jacobites, and his support for the ‘Pretender’ in 1715 led to him being attainted (barred from inheriting titles and property) and his younger brother, James, inheriting the dukedom in 1724. William, along with another of the 1st Duke’s sons, George, would go on to play ever-increasing high-profile roles in the cause during the subsequent risings. The 1st and 2nd Dukes of Atholl, on the other hand, remained loyal to the Hanoverians monarchs, George I and George II, throughout this period.

The Isle of Man also had a complicated relationship when it came to the Jacobites. While no proclamation in support of James Stuart was ever made on the island during the risings of 1715 and 1719, neither was there out-and-out support for George I. The House of Keys, in particular, showed little enthusiasm in co-operating with Governor Horne when it came to arranging the armament of the isle. The Keys also dragged their feet when Horne asked them to pass a law making it a treasonable offence to drink a toast to James Stuart, or utter anything that could be regarded as disloyal to the King. In fact, no such law ever made its way on to the island’s statute books before the Isle of Man’s revestment into the British crown, in 1765. By 1745, however, the 2nd Duke of Atholl was Lord of Man, and the Keys would be far more amenable, perhaps mirroring the Duke’s own need to demonstrate loyalty to the Hanoverians.

It would also be remiss of me not to mention that it is fairly well-documented that Manx merchants and smugglers (often one and the same) forged links with Jacobite sympathisers throughout this period. The island’s smuggling network was used to send messages and instructions, and no doubt ferry goods, between actors in the cause.

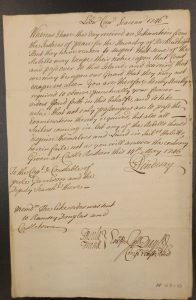

Letter from James Murray to the Duke of Atholl, 12 August 1745 (AP X11-28) [Click images to enlarge & read.]

The first we hear of the Jacobite rising of 1745, in the Atholl Papers, is in a letter from the former Governor of the Isle of Man, James Murray (Receiver General of Scotland), to the Duke of Atholl, sent just days before the ‘Bonnie Prince,’ Charles Stuart, raised his father’s standard at Glenfinnan and proclaimed him King James III. By the tone of the letter, it is clear that Murray did not see the landing of a small Jacobite force on Scottish soil as a credible threat, regarding it purely as a ploy to draw British troops away from the Low Countries (War of the Austrian Succession).

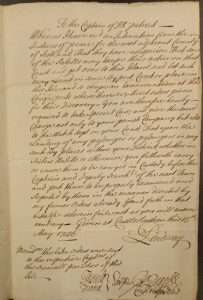

The current Governor, Patrick Lindesay, however, took the news of an insurrection far more seriously. In a letter to the Duke in early September (AP X11-31), Lindesay reported that upon being informed of what was happening, he gave strict instructions for the landing places on the island to be watched. He also proposed the idea of examining strangers that arrived on the isle, which until that point he had shied away from ordering, given the island’s unique position as a haven for those whose ‘private affairs [were] in disorder,’ and a place to reside until such matters were resolved; all of which usually provided a benefit to the isle. The Duke’s response was sent on 14th September from Edinburgh (AP X11-29), days before the city was taken by the Jacobites, informing Lindesay of the rebels’ position and the possibility of them dispersing amongst the counties lying nearest to the Isle of Man. The Duke goes on to warn Lindesay that fugitives might attempt to take refuge on the island, and if so, to take care to apprehend them so they could be ‘delivered up to justice.’ In answer to the Duke’s letter, Lindesay gave orders for the island’s militias to be put on notice to repel landing forces, the watches to be doubled, and for strangers to the isle to be interrogated on arrival; these orders would go on to be reissued in November 1745.

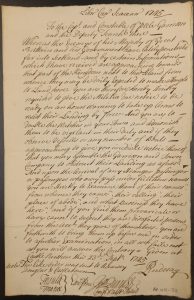

Extract from the Liber Scaccar 1745 – Notice to the Captain and Constable of Peel Garrison, and the Deputy Searcher, 23 September 1745 (AP X11-33) [Click image to enlarge & read.]

The correspondence between the Duke of Atholl and Governor Lindesay goes beyond just the recounting of events in Britain and the issuing of orders, touching also on the Duke’s financial woes and his need to demonstrate loyalty to the Hanoverian cause.

As the Jacobite forces made their way to Edinburgh in late August and early September 1745, the Duke’s brother, William, seized the family estates at Blair Atholl and elsewhere in Perthshire, along with the revenue they generated. By October, the Duke was starting to feel the financial strain of keeping a residence in London, having fled Edinburgh with his wife and daughters just days before the Jacobites entered the city. As such, he sent his steward, Humphrey Harrison, to empty the Isle of Man’s coffers, declaring in a letter that money was a ‘scarce commodity to Scots people at present’ (AP X11-34). In January 1745/46, he accused the island’s moars (rent collectors) of neglecting their duties and generally complained about the dilatory manner in which the revenue was collected and remitted to him (AP X11-41). At one point, there was even talk of the Duke coming to stay on the isle, which raised the whole issue of where to find beds for him and his family, as there was a distinct lack of them on the island, though this idea appears to have been dropped once the Jacobites were on the back foot.

Once the Jacobites had concluded their brief sojourn to England in early January 1745/46, the Duke of Atholl, desirous to show his loyalty to George II, informed Governor Lindesay of his intention to accompany the pursuing Hanoverian forces to Scotland, stating, ‘I think it incumbent upon me to show all the zeal I can for His Ma[jes]ties service in that country,’ and ‘be in the way of doing all in my power upon this occasion’ (AP X11-41). But the Duke also had to be wary of any actions by those under his lordship on the Isle of Man, however trivial, which might call into question his loyalty. Therefore, when the Reverend Thomas Christian, Vicar of Kirk Marown, was brought before Lindesay in early May, accused of stating James Stuart ‘was and is the right heir to the crown of Great Brittaine’ (AP X3-9), the Duke’s response to Lindesay was, ‘I make no doubt but you will have him punished as far as the laws of the isle will admit’ (AP X3-18). However, as no law had been passed on the island that made his statement an act of treason, the worst Christian suffered was a temporary suspension by the Bishop of Sodor and Man.

Keen to demonstrate his loyalty in any fashion, the Duke of Atholl had a copy of all the orders issued by Governor Lindesay on the Isle of Man, during the uprising, printed in the Edinburgh newspapers in the summer of 1746.

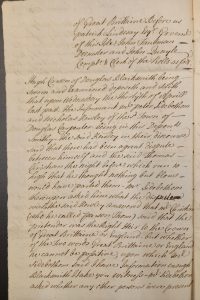

Extracts from the Liber Scaccar 1746 regarding the Reverend Thomas Christian (AP X3-9)[Click images to enlarge & read.]

News of the Jacobites’ defeat at the Battle of Culloden, in April 1746, gave Governor Lindesay and the Isle of Man the opportunity to also demonstrate their allegiance to the King. According to Lindesay, unconfirmed reports of the rebels’ defeat led to ‘great rejoyceings’ on the island, with ‘fiddles and fires’ lasting three days and nights, and ‘much drunkenes amongst the lower sort’ (AP X3-6). Whether this is proof that the Manx inhabitants were actually in support of George II, and not just using the news as an excuse to go on a three-day bender, is up for debate. But, once reports were confirmed, Lindesay arranged a number of official activities to celebrate the victory, including: the displaying of flags, the discharge of canon at Castle Rushen and Derby Fort, bonfires, and a supper for Manx officials and the ‘better sort of the inhabitants.’ The ‘lower sort’ were also not done with their revelries; Lindesay reported that the people of Douglas went around smashing windows on properties owned by Catholics, who in turn had no choice but to put up with the vandalism.

The Jacobites’ defeat at Culloden is not the end of this story in the Atholl Papers, and at least for myself, perhaps brings us to the most interesting part. Following Culloden, the Jacobite army was dispersed and attempts were made to capture those that had taken part in the rising. The Justices of the Peace for the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright sent a warning to Governor Lindesay that rebels might attempt to take refuge on the island, and in response, Lindesay, as he did in September and November 1745, once again issued the order for strangers arriving on the isle to be examined, with the addition that sailors were also to be interrogated, ‘lest any of the rebels should disguise themselves’ (AP X3-10). The captains for the island’s various parishes were also instructed to stay vigilant for people attempting to land at smaller ports or creeks, who might be eager to evade examination at the main towns.

As a consequence of these orders, two young Scottish men by the names of James Napier and William Simpson were detained, after they were seen acting suspiciously in the towns of Ramsey and Douglas, and boarding a Danish ship that had been docked at the island for several weeks. Brought before Governor Lindesay, Napier and Simpson claimed to be chapmen (itinerant traders), who had come to the isle with goods, and a line of credit from Sir John Douglas of Kelhead. Lindesay believed their account, but refused to allow them to leave the island until they provided a certificate from Scotland, which vouched for their story and verified that they had not participated in the rebellion. The Scotsmen procured such a certificate from Sir William Maxwell of Springkell, and they were duly released at the end of June, taking a boat to Annandale, Scotland.

On the surface, this case would look to be quite straight forward, but when you dig into the backgrounds of Sir John and Sir William, it emerges that both were Jacobite sympathisers. In fact, in August 1746, Sir John was arrested after it was revealed that he met with Charles Stuart, back in January at Stirling, and was detained until 1748 before he was released without charge. With this information, it calls into question whether James Napier and William Simpson were indeed simple traders. However, as it appears that they returned to Scotland upon their release, rather than flee to Denmark or elsewhere, I’m inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt, though it is fun to toy with the idea that they were a couple of Jacobite rogues, who pulled one over on the authorities.

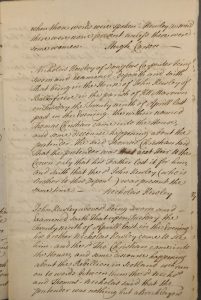

Left: Extract from the Liber Scaccar 1746 – Order from Governor Lindesay to the Captain and Constable of Peel, 14 May 1746 (AP X3-10) [Click image to enlarge & read.]

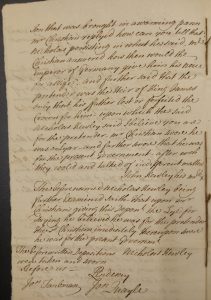

Right: Extract from the Liber Scaccar 1746 – Order from Governor Lindesay to the Captain of Kirk Patrick, 15 May 1746 (AP X3-10) [Click image to enlarge & read.]

It is here that we come to the end of this particular blog, though I will wrap it up by revealing the fates of the Duke of Atholl’s two Jacobite brothers. William, Marquess of Tullibardine, would die in the Tower of London in 1746 after being captured in the aftermath of Culloden. George, however, escaped and made his way to the continent, eventually settling in the Dutch town of Medemblik, where he died in 1760.

The next instalment of the blog will be released at the end of November, and will look at the Isle of Man and its conflict with English and Irish revenue cruisers (it is a far more interesting topic than it sounds!).

Read The Atholl Papers Blog:

The Atholl Papers: The Case of Carolina Elinora Mahon

The 2nd Duke of Atholl’s Inheritance of the Isle of Man

The Atholl Papers: An Introduction to the Project

Gareth Pugh

Manx National Heritage Project Archivist (The Atholl Papers)

Further Reading

Wilkins, Frances. (2002) The Isle of Man and the Jacobite Network. Blakedown: Wyre Forest Press.

Blog Archive

- Edward VII’s Coronation Day in the Isle of Man (9 August 1902)

- Victoria’s Coronation Day in the Isle of Man (28 June 1838)

- Second World War Internment Museum Collections

- First World War Internment Museum Collections

- Rushen Camp: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Hutchinson, Onchan & Peveril Camps: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Douglas Promenade: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Mooragh Camp: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Sculpture collection newly released to iMuseum

- Fishing Folklore: how to stay safe & how to be lucky at sea

- News from the gaol registers project: remembering the men and women who served time in Castle Rushen

- Explore Mann at War: stories of Manx men, women and children in conflict

- We Will Remember Them: Isle of Man Great War Roll of Honour (1914-1918)

- Dr Dave Burnett explores Manx National Heritage geology collection

- Unlocking stories from the Archives: The Transvaal Manx Association

- Login to newspapers online: step-by-step guidance

- ‘Round Mounds’ Investigation Reveals Rare Bronze Age Object