The Atholl Papers: The Post-Revestment Turmoil

At the end of the last Revestment blog, the 3rd Duke and Duchess of Atholl had been forced to sell their lord proprietary rights over the Isle of Man to the British Crown, with the Atholls’ brief reign as the Lords of Mann coming to an end on 17th May 1765. This came about because the British government had finally had enough of what it regarded as the smuggling trade, conducted to and from the isle. However, this was not the end of the Atholls’ relationship with the island or its people, as they retained their landed estates, manorial rights and the ecclesiastical patronage over the Bishopric of Sodor and Man.

The remainder of the 3rd Duke’s period in the Atholl Papers is one of upheaval and change, both for the Manx inhabitants and for the Duke himself. The ‘Mischief Act’ (see The Revestment blog), which came into effect from 1st June 1765, had a significant impact on the Isle of Man’s trade and employment. As for Lord Atholl, he and his Manx representatives had to adapt to his reduced status, which in turn brought about conflict between himself and both the Crown officials and the island’s people, regarding what rights he retained and their extent.

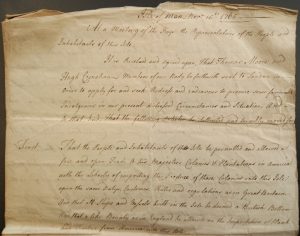

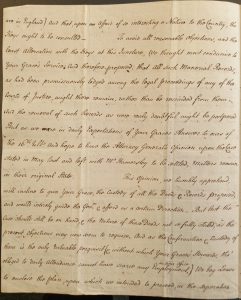

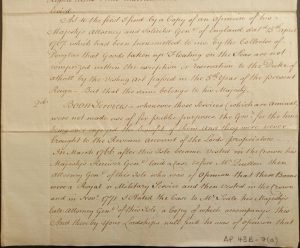

Extracts from An Act for more effectually preventing the mischiefs arising to the revenue and commerce of Great Britain and Ireland, from the illicit and clandestine trade to and from the Isle of Man, also known as ‘The Mischief Act’ (MS 09707/4/35) [Click images to enlarge & read.]

The ‘Mischief Act’ introduced a number of provisions designed to stop goods from the ‘East Indies,’ along with wines and spirits from France and Spain, reaching British shores in a fraudulent manner. As such, these and other wares were banned from being imported to or exported from the Isle of Man, unless under certain strict conditions regarding their transport. To aid in this matter, the Act finally granted the King’s customs officers the authority they had always lacked: the ability to make seizures in Manx waters and on the island itself. It also placed the burden of proof on the commanders of vessels carrying prohibited goods within 9 miles of the isle to demonstrate that their business was legitimate; otherwise they risked their cargo being seized. The Act also encouraged people to inform on those engaged in the illicit trade, offering rewards in exchange.

Following the Revestment and the introduction of the ‘Mischief Act,’ the Isle of Man descended into a ‘panic-stricken condition.’ The merchants tried to rid themselves of East India Company goods and other prohibited items, and when that failed, they hid them around the island from the King’s customs officials, who on arrival turned homes, shops and warehouses upside-down in the search for contraband. The ‘Mischief Act’ would go on to have a significant impact on the smuggling trade, at least in the short term. As trade was a major source of employment on the island, according to various letters and petitions by the House of Keys and others in the Atholl Papers, over the next 5-7 years people began to first leave the towns and then the isle itself for the want of jobs. For instance, a petition by Manx merchants to the Lords of the Treasury in 1772 declared, ‘people daily migrate to foreign parts in quest of bread,’ while also stating houses were falling into disrepair due to the lack of occupancy (MS 09707/4/28). Whether this was true or mere hyperbole is up for debate, given Governor John Wood contradicted such a claim regarding mass migration made in an earlier petition, sent by merchants in 1769. He did, however, concede at the time that if nothing was done to help the island’s revenue, things really would become ‘truly deplorable’ (MS 09707/6/28).

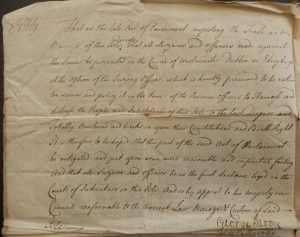

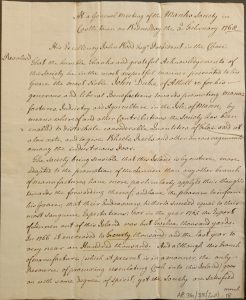

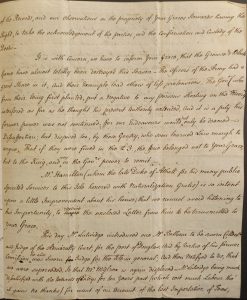

Resolution of the House of Keys, 15 November 1765 (MS 09707/4/11) [Click images to enlarge & read.]

Those with the most to lose, namely merchants, were the ones who took the lead in trying to have the restrictions placed upon the Isle of Man’s trade either removed or relaxed. Merchants such as Hugh Cosnahan, George Moore and John Taubman were also members of the House of Keys. By the time of the 2nd Duke of Atholl’s era, the House of Keys fulfilled a number of roles, including: introducing and discussing legislation; acting as a judicial body to resolve civil legal disputes; and behaving somewhat as a spokesbody for the Manx people. It is in this final capacity that the Keys initially led the charge to protect the island’s interests, though their efforts would be largely unsuccessful.

The Keys had previously attempted to intervene on the Isle of Man’s behalf (really their own) when the Duke of Atholl and the British Treasury were negotiating the sale of the island. At the time, they hoped to gain more advantageous conditions for its trade or some form of recompense for the loss of rights. However, they were ignored by both sides. Undeterred, in November 1765 the Keys passed a resolution to send Hugh Cosnahan and George Moore’s nephew and fellow merchant, Thomas Moore, to Parliament to ‘seek redress and endeavour to procure some favourable indulgences.’ The deputation was given a wish-list of things to obtain, including: free and open trade with Britain’s American colonies; freedom to fish in British waters and receive bounties; the liberty to export wines and brandies to Britain and Ireland; and any charges of smuggling to be tried in Manx courts rather than elsewhere in the British Isles.

It appears that this delegation did not set off for Parliament until the spring of 1766, by which time Hugh Cosnahan had been replaced by the Speaker of the House Keys, George Moore, and the Moores were accompanied by The Reverend James Wilks. Upon arrival, the delegates were aided by the Duke of Atholl’s solicitor, Hugh Hamersley, who secured them a meeting with the Secretary to the Treasury, Grey Cooper. Hamersley also forced the delegates to focus on what they wanted to achieve in that session of Parliament, which boiled down to two things: the resumption of the Manx law courts and relief for the island’s trade. On the first point, it looks like their efforts spurred on the British government to finally begin defining the jurisdictions of the Crown and the Duke’s manorial rights on the isle, and both civil and manorial courts were resumed in the latter half of 1766. As for the point on trade, even though they received receptive noises from the British Treasury and the Speaker of the Commons, nothing came of it and the deputation eventually returned home in June.

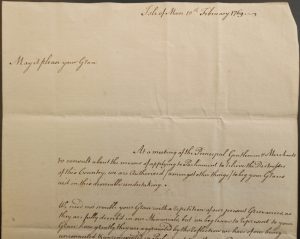

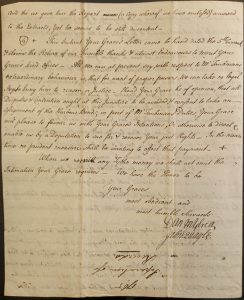

Letter from the Principal Gentlemen and Merchants of the Isle of Man to John Murray, 3rd Duke of Atholl, 10 February 1769 (MS 09707/4/17) [Click images to enlarge & read.]

George Moore would go to Parliament again in early 1767 to make fresh attempts to secure relief for the Isle of Man’s trade, but all he received was a suggestion from Grey Cooper that the island would enjoy extensive trade if it became part of Great Britain, which Moore rejected outright. This would be the last delegation sent by the House of Keys. Even before Moore made his trip to London, members of the Keys were starting to resent the expense being wasted on such a fruitless endeavour, and once there, Moore faced mounting opposition back home from his peers on his handling of the matter.

After the failure of the 1767 delegation to achieve anything meaningful, the House of Keys and various committees of ‘principal gentlemen and merchants’ resigned themselves to sending petitions to the King, the Prime Minister and the Lords of the Treasury between 1769 and 1772. All these petitions focused on removing the restrictions on trade, most of them declaring that the smuggling was no more. The latter was not entirely true, even though officials for the Commissioners of the Customs had reported as such back in 1766. However, just like the delegations, all these petitions appear to have been largely disregarded by the British authorities.

Regardless of the state of the running trade, the British government was not inclined to remove any restrictions that might encourage the Manx to once again go rampant on the smuggling. From the various Acts of Parliament introduced between 1765 and 1772, concerning the Isle of Man, we know that the British government believed the Manx had no business indulging in trade and instead steered them towards the following alternatives: the manufacturing of linen, farming and herring fishing. Linen manufacturing appears to have been the most popular of these alternatives, with quite a number of individuals applying to the Duke of Atholl for licenses to erect flax mills in 1767, and others doing so without his consent. By the end of that year, the Duke’s Stewards, Daniel Mylrea the Younger and John Quayle the Younger, were reporting that linen manufacturing had improved greatly, with the export of linen rising from 12,000 yards in 1764 to 100,000 yards in 1767, and declaring, ‘the generality of the people very happily twin their thoughts to this agriculture’ (MS 09707/6/153). However, in the same letter we also discover how fragile this industry and the Manx economy were, as both appeared to be dependent on the presence of the military companies stationed on the isle. Regarding the news that the Queen’s Royal Regiment was due to leave in January 1768, Mylrea and Quayle informed Lord Atholl, ‘if this regiment, which is ordered to embark the 27th of next month for Gibraltar, is not succeeded by another, this manufacture and the circulating cash will be greatly reduced.’

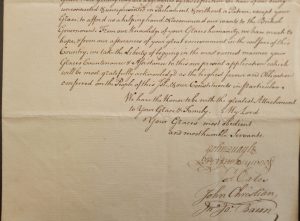

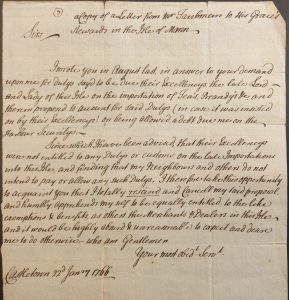

Resolution of the Manks Society, 3 February 1768 (MS 09707/6/90) [Click images to enlarge & read.]

The Duke of Atholl gave what assistance he could to relieve the issues created by the ‘Mischief Act,’ which included putting his support behind the delegations and the petitions sent to Parliament, along with donating funds to the Manks Society to help distribute flaxseed and equipment. However, he also faced his own challenges following the Revestment, which centred around his reduced status on the Isle of Man and the acknowledgement and extent of what were regarded as his manorial rights held there. In the immediate aftermath, he was faced by merchants not paying customs duties still owing from the period November 1764 to May 1765, along with the moars (manorial rent collectors) refusing to collect rents. He also had to contend with tenants no longer believing themselves bound to pay various customary fines or seek licences to erect mills and other buildings. Much of the strife seems to have stemmed from the Crown and manorial records remaining together until the latter half of 1766, at which time they were separated and the manorial records were handed over to the Duke, who was then given permission to establish his courts baron and clear up much of the confusion concerning what he was owed and from whom.

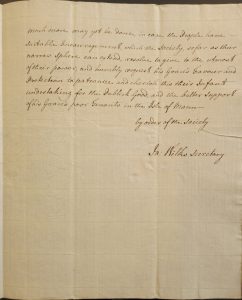

Copy letter from John Taubman to Daniel Mylrea and John Quayle, original dated 22 January 1766 (MS 09707/6/81) [Click image to enlarge & read.]

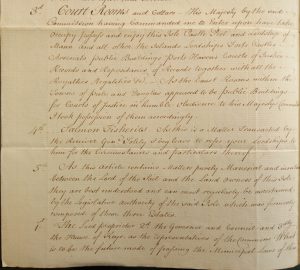

However, the main and most enduring source of conflict regarding the Duke of Atholl’s rights on the Isle of Man came from the newly established Crown officials, many of whom held no former allegiance to the Duke. Contention between the two parties largely revolved around three areas: ownership and hunting of game; rights to the wrecks of the sea; and rights to the boon money. There were other sources of dispute, such as possession over the court rooms and cellars, along with ownership over the salmon fisheries in the bays, but these areas are fairly underrepresented in the 3rd Duke’s papers.

The Revestment saw the arrival of British troops stationed on the Isle of Man, beginning with the Queen’s Royal Regiment. But once in situ, the regiment’s officers got a little over-enthusiastic when it came to hunting grouse and other game birds, almost destroying the whole stock in 1765. To add insult to injury, these officers did so without first obtaining a licence from the Duke, who held claim over game as one of his manorial rights. The actions of these officers also encouraged others on the island to disregard Lord Atholl’s claim with some refusing to pay fines for their misdeeds, even though Governor Wood attempted to intercede on his behalf. Fearing the officers’ behaviour would be left unchecked and the game bird populations ruined once more, the Duke’s Steward, John Quayle, visited the regiment’s commanding officer prior to the 1766 season and outlined Lord Atholl’s rights. This appears to have had the desired effect, as there were no reports of wanton destruction that year or any other, and by 1772 licences were being issued to newly arrived officers. Though this dispute looked to have been resolved, the issue over rights to game would arise again later in the 4th Duke’s era.

Letter from Daniel Mylrea and John Quayle to John Murray, 3rd Duke of Atholl, 26 September 1765 (MS 09707/6/125) [Click images to enlarge & read.]

The Duke of Atholl’s claim over wrecks of the sea and flotsam and jetsam was challenged by Crown officials almost immediately following the Revestment, but came to the fore in the spring of 1767, when the Collector of Douglas seized a number of large barrels containing tobacco, which were found floating off the coast. Though pressed to release the tobacco into the Duke’s Stewards’ custody, the Collector originally refused to do so and wrote to the Lords of the Treasury on the matter, but given that the tobacco was a perishable commodity and the Stewards had a buyer for it, he later agreed to release the goods to them. This concession, however, was on the condition that if the Manx Attorney General later deemed the tobacco to be Crown property, the Stewards would hand over the sale’s proceeds. As such, they declined his offer. Soon afterwards, the Attorney General came to the conclusion that the tobacco belonged to the Crown. The issue over wrecks would rear itself once more in 1773, when 200 casks from a wreck in Dublin Bay made their way across to the island’s shores. However, it appears by this point that some form of compromise had been reached between Crown officials and the Duke’s Stewards: goods that landed were the property of Lord Atholl, while those fished out of the water belonged to the Crown. Even so, this issue continued to remain a source of contention between both parties.

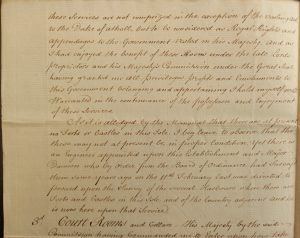

The final area of dispute between the Crown and the Duke was over money received for boon (and carriage). If you know your Ancien Régime history of France, boon service was similar to the corvée: customary unpaid labour owed to the lord of the manor. However, just like the corvée, you could get out of it by paying a fine. The Crown officials challenged the Duke’s claim to this money within a year of the Revestment with the Receiver General, Charles Lutwidge, claiming it to be an appurtenance attached to the castles and forts for their upkeep, which could be traced back to 1405 when the Stanley family were given possession of the Isle of Man. By 1768, it had been ruled by the Attorney General that boon money belonged to the Crown, but the Governor still paid it to the Duke’s Stewards. Even so, there were diminishing returns in the money received as people believed themselves no longer bound to pay what they owed, as a consequence of the Revestment.

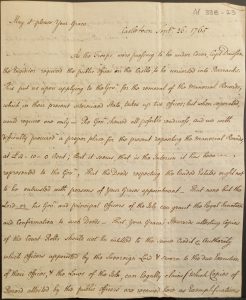

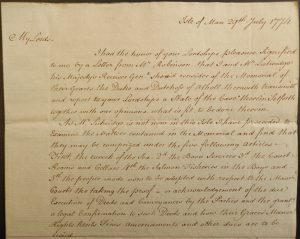

Copy of Governor Wood’s Report to the British Treasury on the memorial of John Murray, 3rd Duke of Atholl, original dated 29 July 1774 (AP43B-7 [Click images to enlarge & read.]

The Duke of Atholl would eventually have enough of the Crown officials infringing upon his rights on the Isle of Man, sending a memorial to the Lords of the Treasury in 1774, which demanded that the rights granted to him via the Act of Revestment be respected. However, matters would be left unresolved as the Duke apparently drowned himself in a fit of delirium in the River Tay on 5th November 1774. Even so, the conflict regarding the family’s rights on the island was not over, as the 4th Duke took on the fight to establish and secure what he believed himself owed, which would carry on for the next 30 years. As part of the British government’s attempts to appease the 4th Duke, he would be made the Governor of the isle in 1793 and remain so until his death in 1830.

Read The Atholl Papers Blog:

The Atholl Papers: The Revestment

The Atholl Papers: Project Update

The Atholl Papers: Captain Dow and the Dutch Dogger

The Atholl Papers: The Jacobite Rising of 1745

The Atholl Papers: The Case of Carolina Elinora Mahon

The 2nd Duke of Atholl’s Inheritance of the Isle of Man

The Atholl Papers: An Introduction to the Project

Gareth Pugh

Manx National Heritage Project Archivist (The Atholl Papers)

Further Reading

Moore, A. W. (1992) A History of the Isle of Man Volume 2. Manx National Heritage.

Winterbottom, Derek. (2007) Profile of the Isle of Man. Sweden

Blog Archive

- Edward VII’s Coronation Day in the Isle of Man (9 August 1902)

- Victoria’s Coronation Day in the Isle of Man (28 June 1838)

- Second World War Internment Museum Collections

- First World War Internment Museum Collections

- Rushen Camp: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Hutchinson, Onchan & Peveril Camps: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Douglas Promenade: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Mooragh Camp: Second World War Internment on the Isle of Man

- Sculpture collection newly released to iMuseum

- Fishing Folklore: how to stay safe & how to be lucky at sea

- News from the gaol registers project: remembering the men and women who served time in Castle Rushen

- Explore Mann at War: stories of Manx men, women and children in conflict

- We Will Remember Them: Isle of Man Great War Roll of Honour (1914-1918)

- Dr Dave Burnett explores Manx National Heritage geology collection

- Unlocking stories from the Archives: The Transvaal Manx Association

- Login to newspapers online: step-by-step guidance

- ‘Round Mounds’ Investigation Reveals Rare Bronze Age Object